24 Apr, 2017

Thailand’s bid to “disrupt the disrupters” in legal limbo

Bangkok – Taxi drivers in many Thai tourist cities have long been well known for ripping off passengers — meters that suddenly “did not work”, roads that were suddenly “closed for repairs” requiring the driver to take a longer route, shops that had “just shut down” so that the driver could take the passenger to another shop, etc. etc. Hampered by language restrictions, and lack of recourse, many tourists in the “Land of Smiles” just smiled and put up.

Then came the sharing economy. The system struck back. Nice clean cabs, hassle-free, point-to-point service, a rating system and a fare structure that functioned along the same lines as low cost airlines — when demand was high, so was the fare.

Uber entered the Thai market in 2014. The following year, Bangkok taxi drivers complained their business went down by 30%. Rather than analysing the root cause — their own poor service — they blamed Uber, the disrupter. Like wailing babies, they went wringing their hands to mama-san, the Royal Thai Government, seeking redress. Unfortunately, the Land Transport Department (LTD), which couldn’t do much to curb taxi-drivers’ rip-offs, now couldn’t do much to bar their tormentor either.

How the tables turned.

On April 20, 2017, a group of Chiang Mai minibus drivers filed a complaint in a local court to demand that the LTD “enforce the law” against Uber. The minibus drivers say their income has now fallen to 700 – 800 baht per day which, after deducting petrol costs, leaves them with only 100 – 200 baht. The same day, a group of Bangkok taxi drivers were due to lodge a cease-and-desist complaint against Uber in a local court.

On April 19, 2017, the Foreign Correspondents Club of Thailand (FCCT) held a panel discussion on the topic of “Disrupting the Disrupters”. Noting that “the Thai government is having trouble coming to terms with these ‘disruptive’ services that successfully poach business from established enterprises and service providers,” the FCCT announcement said the panel would focus on the questions: How much regulation is desirable? Should such services be controlled or shut down? Whose interests should be uppermost – the consumer’s or the provider’s? Between threats of legal action and a growing number of satisfied clients, who will emerge as victors in this strife?

The primary conclusion of the discussion, which focussed on taxi-services and Airbnb, was that a state of legal limbo exists, with both the public and private sectors unable to enforce their own laws and regulations. Amidst the dithering, the sharing economy entrepreneurs roll on.

Panelists: Ms Thitirat Thipsamritkul, law lecturer at Thammasat University, Mr K.Siri Tadpring, representative of the Land Transport Department, and Mr Samphop Bunnag, president of the Property Management Association of Thailand.

The panel discussion under way with Mr Teeranai Charuvastr, the moderator at the right.

Like low-cost airlines and online travel agents, tech-savvy entrepreneurs have identified and filled a market need. Like legacy airlines and travel agents, the hotels and cabbies didn’t know what hit them. Governments found their rules and regulations being too outdated, and their law enforcement agencies unprepared and untrained to handle the changes. The legacy private sector cries foul and wants the public sector to enforce the law, but is also incapable of self-regulating itself.

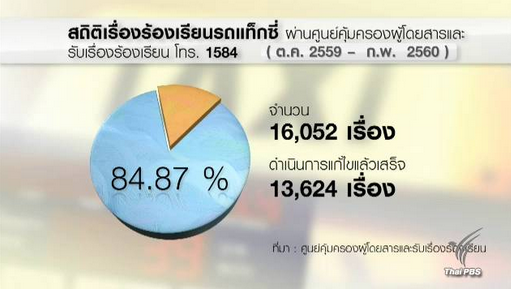

That there is a problem with the legacy taxi services is undeniable. Between October 2016 and February 2017, the LTD recorded 16,052 complaints (or roughly 107 per day) against taxis of which it claimed that 13,624 were investigated and settled (translation of the chart below). The top three complaints were: 1. Refusal to accept passengers 2. Not using the meter 3. Tampering of the meter. In the same period, the LTD reported more than 43,000 people used ride-sharing services.

At the FCCT discussion, Mr K.Siri Tadpring, an LTD representative, said that although the department feels Uber is in violation of the law, the LTD prefers to have a dialogue. He said in previous talks, the ride-sharing company has argued its case by highlighting the benefits to commuters, but the LTD also has to protect the interests of the taxis. The Department asked Uber to register as a taxi service, but Uber said it is not a taxi company but rather a ride-sharing application. The LTD said ride-sharing means a free service, not one that charges a fare and and also changes it by the time of the day. That, the LTD feels, is not fair to the taxis.

Mr K.Siri said they studied what other countries are doing and found that Uber drivers and their vehicles have to be licensed and registered. The fares have to be regulated too.

He insisted that the department is not against innovation and sees a future in the sharing economy. Asked if the LTD would crackdown on the many Uber drivers plying the streets of Bangkok, he said only if there is a complaint. But no offensive or sting operations will be undertaken.

I asked Mr K.Siri how the public could expect the LTD to enforce the law against ride-sharing services when it had failed to do so against taxi-drivers ripping off tourists. He said the LTD has always been taking action against errant taxi-drivers and blamed poor communication by the LTD for the lack of interest by the public and the media. He said he would seek to rectify this. Uber too has good and bad drivers but this does not make the media, he said, adding that the LTD also has set up a hotline number to report complaints, with a promise of quick action.

I asked if the LTD would move against Uber if the court rules in favour of the Bangkok taxi drivers and bans the service, he indicated that it would be difficult. Instead, he voiced hope that Uber would heed the court ruling and wind up of its own accord, “as it has done in other countries.”

While Uber is providing a simple, one-off service, the Airbnb case is more complex, even though the issue is the same: Interpreting and enforcing the law.

At the FCCT discussion, Mr Samphop Bunnag, president of the Property Management Association of Thailand, said Airbnb will have far-reaching consequences for urban residential buildings by blurring the line between hotels and residences. He said the condo business in Thailand only emerged 30 years ago before which the Thai people lived in communities with family bungalows. Today, condos are being bought by people to live or to invest, with a bigger increase in the percentage of those buying for investment. Different categories of condos had emerged in resorts and cities, accompanied by other selling methods such as time-sharing. Over time, the rental system also changed, from periods of one-two-three years to daily rentals.

Mr Samphop said Thai law defines the condo as a place of a residence and that if it is rented out for periods of a month or less, a separate license is needed. “That means if you rent a unit out for less than a month, you are breaking the law. But Airbnb is advertising rooms for daily rent. In my opinion, it’s wrong. It’s against the law. So why is Airbnb still doing business?”

He said those who rent out their condo units for daily usage create numerous problems for other co-owners in the condo who are using their units only for residential purposes. Firstly, the constant change in occupants violates the privacy of the other condo residents. Second, some Chinese groups using Airbnb condo units are known to make a mess of the swimming pool and fitness centre but don’t have to pay for fixing of any the problems. That cost is eventually borne by the other condo co-owners, which is not fair. Thirdly, security, no-one knows who is who. “Maybe the unit is being used by terrorists or criminals,” Mr Samphop said.

Finally, he said a hotel require numerous licenses such as fire protection, insurance, all of which is a cost to the investor. “But if condo owners put their units out for daily rental, they don’t incur any such costs.” He added, “I believe the government has to solve the problem, not to create a new law but to enforce the existing law.” That itself is a problem. Many meetings have been held, but they become discussion forums, with no conclusions or follow-up results, Mr Samphop said.

However, he admitted that the private sector too fails to enforce its own regulations. He is aware of at least one building where an entire floor has been let out for Airbnb usage. The owner of that space is the chairperson of the condo managing committee. “We, the outsourced company, have to be careful as we can lose the contract. There is a conflict of interest but we the out-sourced company and juristic person cannot do anything.”

The third panelist, Ms Thitirat Thipsamritkul, law lecturer at Thammasat University, a specialist in international laws who has been closely following the global stand-offs between disruptive businesses and legal institutions, cited the various kinds of sharing economy that have emerged and evolved over the years. She said these included those offering both products and services, as well as those which are free and for-profit. She said that the sharing economy will continue to grow. “It will never stop. Even if we enforce the law we cannot stop the growth.”

She said the key question is: “Do we need new laws for new technology? No, it’s not necessary. All forms of technology are disruptive. Even the printer made it possible for writers to publish their own books but also created copyright infringement problems. Yet, we did not have a new law to regulate printers. Existing laws can be applied but they need a new interpretation. The existing laws don’t fit the new technologies.”

She said the sharing-economy companies match demand and supply efficiently. They also build two-way trust and confidence between the transacting parties, such as via Uber’s tracking and rating systems. They also reduce the transaction cost in the traditional economy by excluding the middle man. “This becomes very hard for government to intervene and regulate. We want free and fair competition and not big fish eating the small fish.” However, Ms Thitirat said Thailand needs to find ways of taxing the online service providers such as Agoda and Uber.

“We have a very confusing situation right now. On the one hand, we talk of advancing a digital economy and Thailand 4.0 but on the other hand we have many regulations that obstruct a proper functioning of the digital economy. Even within the government there are differences about how to handle this,” she said. The situation is not helped by the fact that there is no common international law for the internet, with different countries having different laws.

The moderator, Mr Teeranai Charuvastr, a senior editor with Khao Sod English newspaper, said that Grab, Airbnb and Uber had all been asked to appear on the panel, but said they were not available. Uber specifically said it was “not comfortable sharing the panel with other partners,” Mr Teeranai said.

Either way, technology is forcing change. If you can’t beat them, join them. The Bangkok taxi cooperative network has launched its own Smart Taxi app. The LTD is developing two of its own apps, with a higher and mid level of taxi services to compete with Uber. On 26 April, the LTD has summoned the taxi companies for a more thorough discussion of their concerns. It is doing a detailed study of the taxi services in Thailand, to cover everything from the standards of vehicles to be used, supervision of drivers, service users, as well as taxation with comparison with similar services in other countries such as Malaysia and Singapore. The study will take 6-12 months and help identify whether existing laws need to be revised or “a new pattern of passenger service is necessary,” according to the Ministry of Transport.

Pending completion of the study, the ministry is “requesting the cooperation” of Uber to cease services. An Uber spokesperson was quoted by the Thai PBS media network as declining the request.

Editor’s Note: Did you find the above report useful? Will it help you in some way? No other travel trade media attended this panel discussion. It took me two hours to cover the event, and another six hours to review my notes, write and edit this report. If you would like to equitably share the benefits in a sharing economy, please make my effort worthwhile: Click here.

Liked this article? Share it!