16 Apr, 2024

Travel & Tourism pays the price of not investing in peace

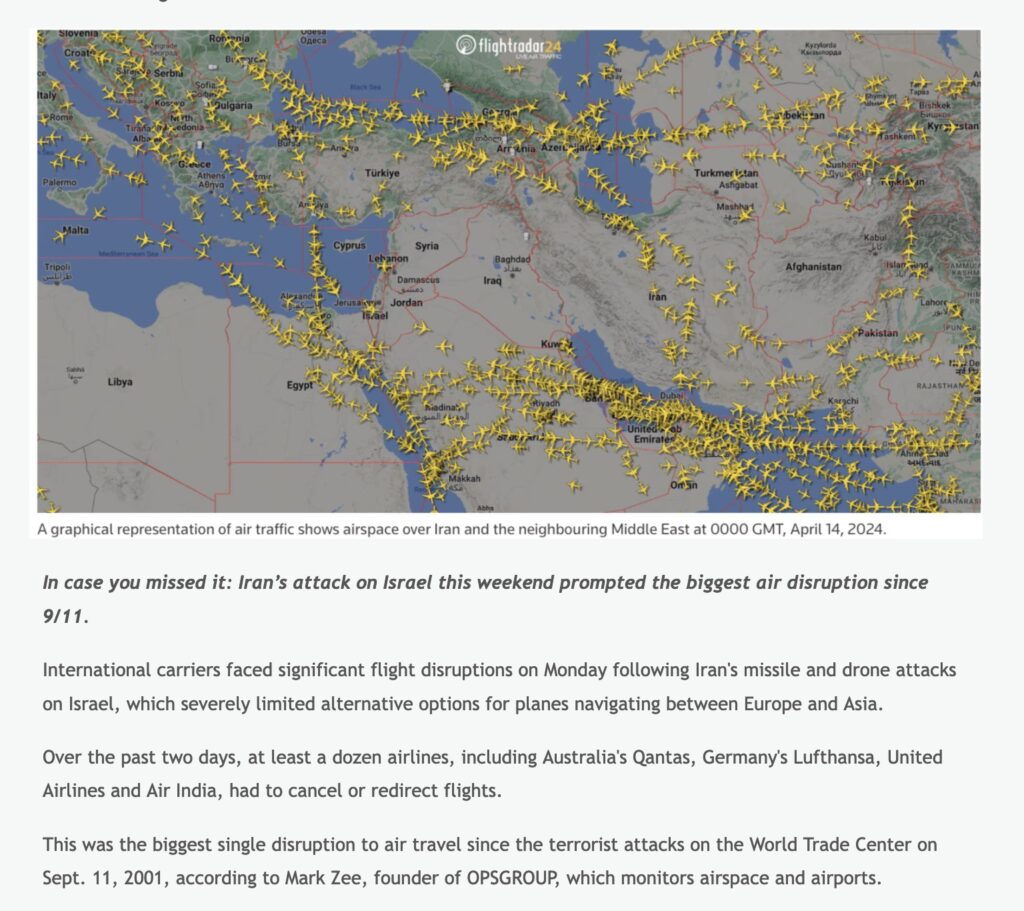

Bangkok — The global travel & tourism industry is waiting with bated breath to see what happens next in the Middle East. After ignoring the rising geopolitical tension for months, the industry was jolted out of its comfort zones by a sharp escalation which threatened to again bring the entire house crashing down. Climate change and AI have faded on the radar screens. As the threat is set to loom large for years ahead, the question is how should Travel & Tourism navigate the geopolitical storms and start charting a course towards true sustainability, especially SDG #16 (Peace, Justice and Strong Institutions).

At this inflection point in global history, learning the lessons of history would be a good start.

Since the 1970s, the fortunes of Travel & tourism have ebbed and flowed in direct relation to geopolitical developments. Yet, the industry has done little or nothing to elevate the value and consciousness-level of that relationship as a force for peace-building. Instead, it has concentrated disproportionately on the numbers game.

‘P’ for Profit is NOT one of the 5Ps of sustainable development (People, Planet, Prosperity, Peace and Partnership). Yet, that missing ‘P’ has been clearly accorded more priority than the others.

Exactly 30 years ago this week, on 18 April 1994, the Pacific Asia Travel Association (PATA) annual conference in Korea kicked off with a keynote speech by the late President George W Bush Sr in which he pleaded for Travel & Tourism to invest in peace. Realising its historic value, I carefully preserved the PATA conference daily featuring that headline.

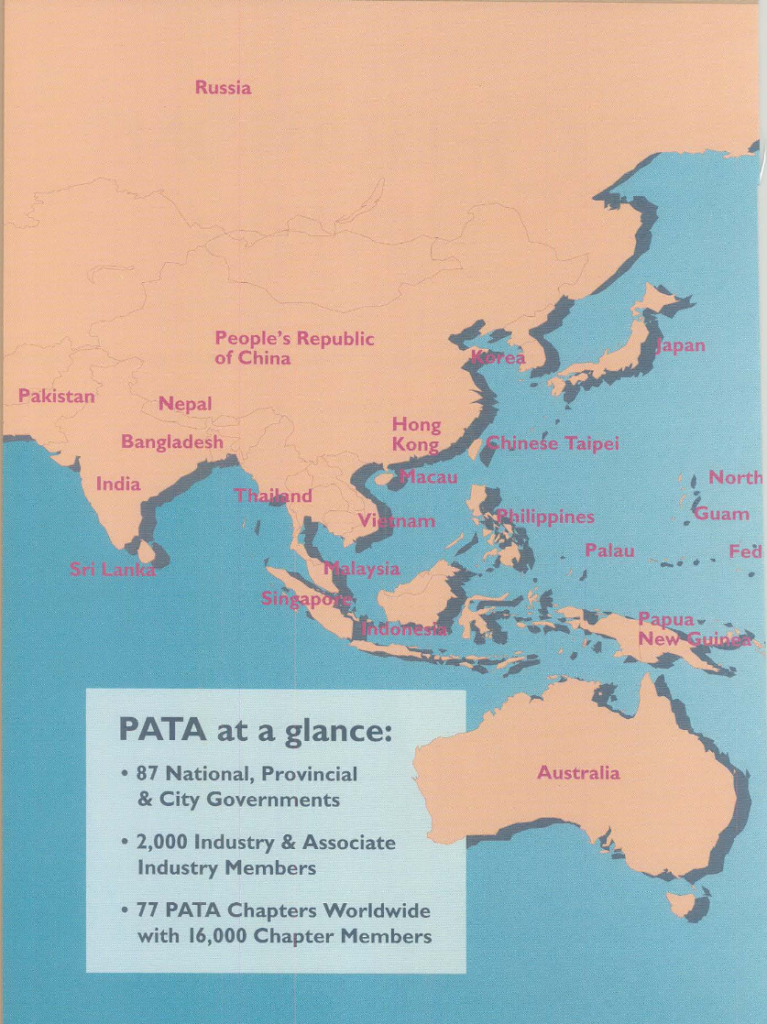

A deeper look in my unmatched historical archives showed that in 1994, PATA had a membership of 16,000 chapter members, 2,000 industry and associate members and 87 national, provincial and city governments. It was the world’s pre-eminent travel grouping, well ahead of both the World Travel & Tourism Council (which had only just been founded in 1990), and what was formerly known as the UN World Tourism Organisation, then undergoing a heavy-duty revamp under the late Secretary-General Antonio Enríquez Savignac.

In his speech, Mr Bush described an operating environment not much different from today’s. He mentioned an “increasingly unpredictable world” peppered by “strange, tough leaders.” He talked about the evolving world order after the 1989 fall of the Berlin wall, the rise of China, the tensions in the Korean peninsula and, of course, the Middle East situation in the aftermath of Operation Desert Storm, a military campaign against Iraq over which he presided.

In the midst of all this, his message to PATA was clear. PATA must use its status and clout to act as an “agent of peace.” He added, “I view PATA as a peace organisation. I encourage you to stay in the forefront, fighting for change that will benefit the organisation and peace throughout the world.”

It was the first time a leader of that stature had flagged that linkage at a global travel conference. Regrettably, those words fell by the wayside, like numerous other PATA keynote speeches.

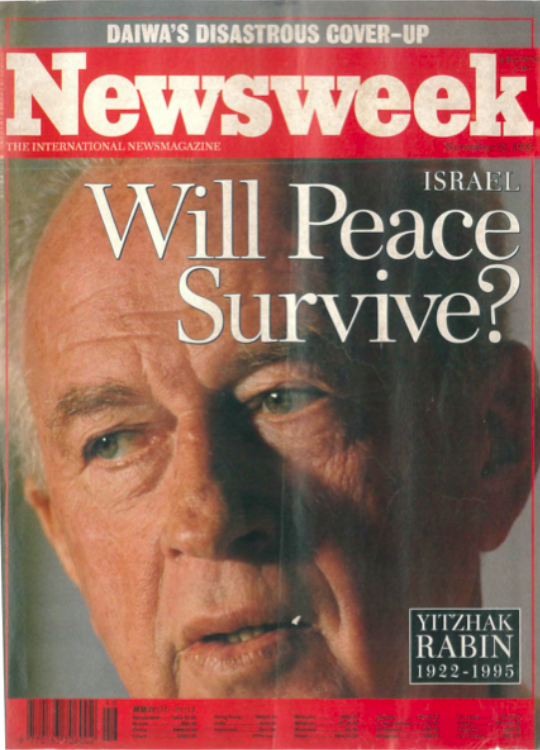

In fact, in 1994, a very strong peace-and-tourism nexus was emerging in Israel-Palestine. In 1991, Mr Bush had lost the US Presidential election. His successor as of Jan 1992, the charismatic young Bill Clinton, was trying hard to forge a broader peace deal between the late Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin and Palestinian leader Yasser Arafat under what was then known as the Oslo Accords.

Both geopolitical events of that era impacted Travel & Tourism, for better and for worse. Operation Desert Storm stalled Travel & Tourism flows for several months. Conversely, the Israel-Palestine peace talks saw a boom in tourism to the Holy Land. That ended along with the “peace process” following Gen Rabin’s Nov 1995 assassination by a Jewish fanatic terrorist.

Historically, multiple events exemplify the positive/negative linkage between geopolitics and tourism.

On the negative side, tourism has been hit by the 1990-91 Iraq War, the September 2001 attacks, the 2003 second Iraq war, the Rabin assassination, conflicts in Sri Lanka and Myanmar, domestic revolutions and upheavals in other countries such as Nepal, Thailand, Indonesia, the Philippines and many more. The India-Pakistan conflict has dragged down the entire South Asian region for decades.

On the positive side, Travel & Tourism has benefitted from the end of the Indochina wars in 1979 and the fall of the Berlin wall 10 years later in 1989. Countries such as Ireland, Bosnia-Herzegovina and Rwanda also offer ample proof of how tourism leads the nation-rebuilding process when peace replaces conflict.

Today, the two major raging conflicts are Ukraine-Russia and Israel-Palestine. Both are impacting Travel & Tourism. But the “industry of peace” does not really care as long as they remain “localised” and the post-Covid numbers continue bouncing back. Never mind how many lives are lost or how much suffering they cause or how much money is squandered. Only when the situation threatens to become globalised and disrupt travel flows does anyone begin to pay attention.

In other words, the industry sees no value in promoting, sustaining and nourishing the benefits of peace and harmony as a permanent contributor to human stability, security and safety.

It only wakes up when corporate bottom-lines and the visitor arrivals count are threatened.

Why?

Why do Travel & Tourism leaders, decision-makers, strategic planners and policy-planners fail to recognise and respect the value of the peace-tourism relationship?

Could it be because it is never taught as a subject by academia? Promised as a deliverable by politicians? Reflected in the stock prices or the quarterly profit-and-loss reports? Discussed in corporate boardrooms? Cited in speeches by NTO and airline executives?

Why does bean-counting take priority over building peace and harmony — the root of sustainability?

This obsession with delivering numerical, financial and statistical results was a major reason why “overtourism” become the source of much consternation. Somewhat too late, the industry woke up to the damaging effects of unbridled growth, congestion and over-development. But at least it did wake up.

That has yet to happen for the cause of building peace through tourism.

Looking back, Mr Bush’s lofty speech about “investing in peace” and plea for PATA to “stay in the forefront, fighting for change that will benefit the organisation and peace throughout the world” was a waste of time and money. Sure, it gave PATA some honour and prestige, and elevated the status of the annual conference. But that was it.

So, as PATA gets set for yet another annual conference in May 2024 and the election of a new team of office-bearers, it may be a good idea to compare the diminished and devalued status of the association itself, as well as the quality of content and attendance of the annual summit, to the 1994 event. Then do the same for the global scenario and ask whether Travel & Tourism can afford to keep its head stuck in the sand about the highly unstable, volatile and unpredictable operating environment.

The Middle East crisis is set to be biggest threat to peace for at least another generation. To claim to have the interests of the Gen Z at heart while ignoring this broader threat to its future is a contradiction in terms. Climate change and AI pale by comparison. It is now the over-arching responsibility of this current generation to learn the lessons of history and create platforms for serious discussion and debate about investing in peace.

At the height of the Covid-19 catastrophe, the buzzwords were “Building Back Better,” creating a “New Normal” and converting a “Crisis into an Opportunity.” It is time to walk the talk. Or else the post-Covid “resilience and recovery” euphoria is likely to prove highly illusory.

Liked this article? Share it!