16 Jul 2013

Little respite seen for youth, low-skilled workers worst hit by jobs crisis in OECD countries

Paris, (OECD media release) 16/07/2013 – Unemployment in OECD countries will remain high through 2014, with young people and the low-skilled hit hardest, according to a new OECD report.

Download the data in Excel for all OECD countries |

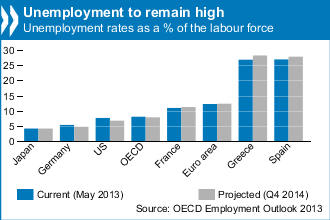

The Employment Outlook 2013 says that jobless rates will fall only slightly over the next 18 months, from 8.0% in May 2013 to 7.8% at the end of 2014, leaving around 48 million people out of work in the 34 OECD countries.

The report reveals big, widening disparities between countries. Unemployment in the US is projected to fall from 7.6% in May 2013 to below 7% by the end of 2014. In Germany, the unemployment rate will decline from 5.3% to under 5%. But in the rest of Europe, joblessness will remain flat or even rise in many countries. By end 2014, unemployment is expected to be just over 11% in France, around 12.5% in Italy, and close to 28% in Spain and Greece.

Says the report, “Concerns are growing in many countries about the strains that persistently high levels of unemployment are placing on the social fabric. Over five years have passed since the onset of the global financial and economic crisis but an uneven and weak recovery has not generated enough jobs to make a serious dent in unemployment in many OECD countries.”

“The social scars of the crisis are far from being healed,” said OECD Secretary-General Angel Gurría at the launch of the report in Paris. “Many of our countries continue to struggle with high and persistent unemployment, particularly among youth. Therefore, the recent commitment by OECD Ministers to do more to help youth, as set out in the OECD Action Plan for Youth, is an essential tool in our fight against the scourge of joblessness.”

The hardship of the crisis has not been shared equally, says the report:

- In many OECD countries, job losses and earnings losses have been concentrated in low-skilled, low-income households more than in those with higher skills and incomes. In the large emerging economies, employment was less affected by the crisis but many workers remain trapped in low-paid, insecure jobs with little social protection.

- Young people continue to face record unemployment levels in many countries, with rates exceeding 60% in Greece, 52% in South Africa, 55% in Spain and around 40% in Italy and Portugal.

- People on insecure, short-term contracts, especially youth and the low-skilled, were often the first to be fired as the crisis hit and have since struggled to find a new job.

- Older workers have fared much better in the crisis, with their job rates rising or falling only modestly. Many are retiring later for a variety of reasons, including better health, the closure of access to early retirement schemes and also financial pressures. New evidence in the Outlook shows that this has not been at the expense of the young. Bringing back early retirement schemes or relaxing rules for disability or unemployment benefits for older workers would be a costly mistake, says the OECD.

Governments should tackle the jobs crisis with a combination of macroeconomic policies and structural reforms to strengthen growth and boost job creation. Over the past few years, a number of countries, including Greece, Italy, Mexico Portugal and Spain, have introduced ambitious reforms to reduce the gap in employment protection between workers on temporary contracts and those on permanent contracts. These reforms have the potential, if fully implemented, to promote a more inclusive labour market and a better allocation of resources leading to enhanced productivity performance.

A growing number of people, having been unemployed for a long time in the crisis, risk losing their entitlement to unemployment benefits and having to fall back on less generous social assistance. Minimum income benefits may need to be strengthened to support families in hardship, especially where long-term unemployment remains very high.

The Outlook also says that activation policies in all OECD and large emerging economies must be strengthened to help and encourage the unemployed and other inactive groups find rewarding and productive jobs. In particular, adequate resources must be devoted to active labour market policies, such as help with job hunting and training, and ensuring that these are sufficiently funded. Spending per jobseeker has fallen sharply since the crisis, by almost 20% on average in the OECD, as pressures on public budgets have risen.

Excerpts from the report:

<> Increasing income inequality. While the upwards pressure on earnings inequality has eased in the wake of the crisis (presumably due to the concentration of job losses among low- paid workers), broader measures of inequality based on household income from work and capital have tended to widen. However, these effects were mitigated by changes in public transfers and personal income taxes, which were quite effective in many countries in limiting rises in inequality in terms of disposable income (i.e. the effective incomes that households can spend).

<> Early retirement schemes failed: During the 1970s and 1980s, many governments in OECD countries started to actively encourage older workers to withdraw from the labour force by introducing early retirement schemes. Driven by concerns over high and persistent unemployment rates, the hope was that by actively encouraging older workers to retire early this would open up job opportunities for other groups, and particularly youth. Similarly, some OECD countries eased access to disability benefits following previous recessions, in effect allowing labour market difficulties to become one of the criteria for entry, rather than exclusive medical criteria. Both early retirement and easier access to disability may account to an important extent for the large reduction in labour force participation rates observed in the aftermath of major economic downturns in the 1970s and 1980s . However, the expectation that this would free up jobs for youth was not borne out in practice in terms of either higher employment rates or lower unemployment rates for youth (OECD, 2006b).21 Consequently, policies that have actively promoted the permanent withdrawal of older workers from the labour force have not delivered the desired results. Instead, they have yielded large and long-lasting adverse consequences for the public purse and potential economic growth.

<> Health-care: Older workers may increasingly have managed to stay healthy for longer as a result of several important developments. First, changes in the composition of jobs have prevented older workers from becoming disabled or have induced older workers to postpone their retirement decisions. For example, as a result of structural changes, the composition of employment may have shifted away from physically demanding and dangerous jobs in mining, construction and manufacturing to services. Second, secular trends in preventive health systems could also play an important role in raising the physical age at which persons can remain productive at work. Apart from developments that allow older workers to stay in better health, general increases in health and safety standards at work may also play a role.

<> Doing more with less: The initial policy response to the surging labour market problems and social needs emanating from the crisis was to set up or strengthen support programmes to protect the most vulnerable groups. This has helped to cushion household incomes and, in turn, to support aggregate demand and employment. However, these programmes are under increasing strain in many countries: social welfare needs have increased since the beginning of the global crisis, but the fiscal resources available to meet these demands have often shrunk. In a nutshell, governments are facing the challenge of “doing more with less”. The appropriate response must be a combination of social and activation policies that provide adequate income support for the most vulnerable groups, while encouraging and helping these groups to either return to work or to improve their job readiness and employability.