3 Aug, 2017

Lessons from the Malaysian National Museum for the future of ASEAN

Kuala Lumpur — As a history buff, I enjoy visiting museums. These homes for the preservation of history are the best places to learn the lessons of history, and perhaps avoid repeating past mistakes.

Last week, I visited the Malaysian National Museum in Kuala Lumpur for the third time. This visit had a special significance. It was devoted specifically to help me better understand the tourism slogan “Malaysia Truly Asia” within the context of the 50th anniversary of ASEAN and see what can be learnt to realise the ASEAN integration slogan of “One Vision One Identity One Community” over the next 50 years.

Malaysia is a very strategically located country, at the crossroads of the world’s most important sea-lanes. Like other ASEAN and Asian countries, it is a hybrid product of cultures, colonialism and wars. Over the past 10 centuries, it has been under Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms, Islam, the Portuguese, Dutch, British colonialists and Japanese imperalists.

Today, it is a Muslim-majority country with significant percentages of Hindus, Buddhists, Christians and Sikhs. It’s not unusual to bump into a Sikh Malaysian who speaks Mandarin or a Chinese Malaysian who is well-versed with Islamic culture. In the cities, just about everyone speaks English.

This rich diversity of culture, history and heritage is a tourism asset and driver of economic development. But as the museum visit clearly signaled, the asset can quickly become a liability. All it takes is a deflection point.

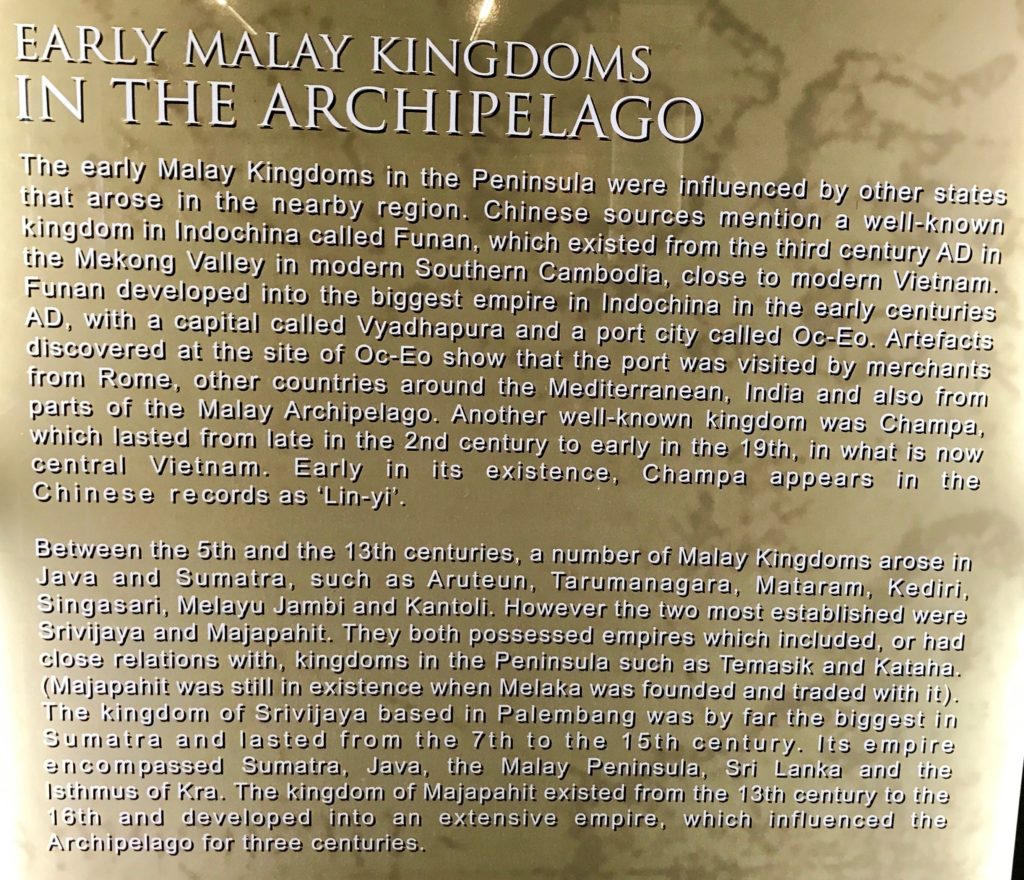

The museum begins with the pre-historic era, including the geographic formations of the land. Once it enters the history era, the museum plaque says this:

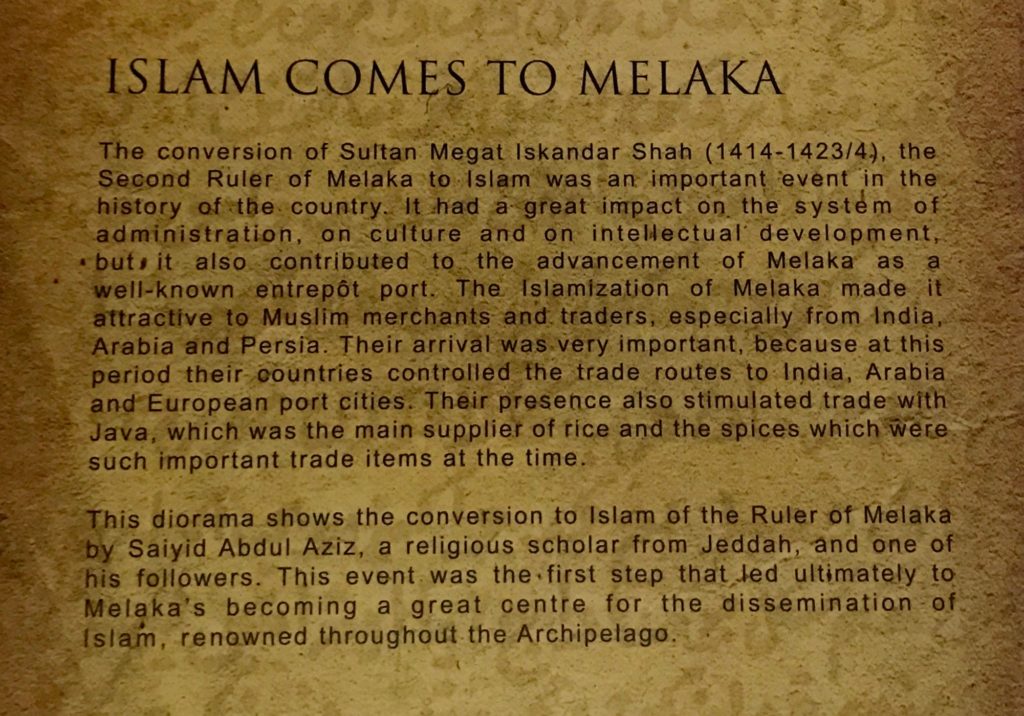

Then came Islam. This transition with the conversion of the Sultan of Melaka during the period of his reign (1414-24), roughly 600 years ago.

Islam spread through the region during 15th-16th centuries.

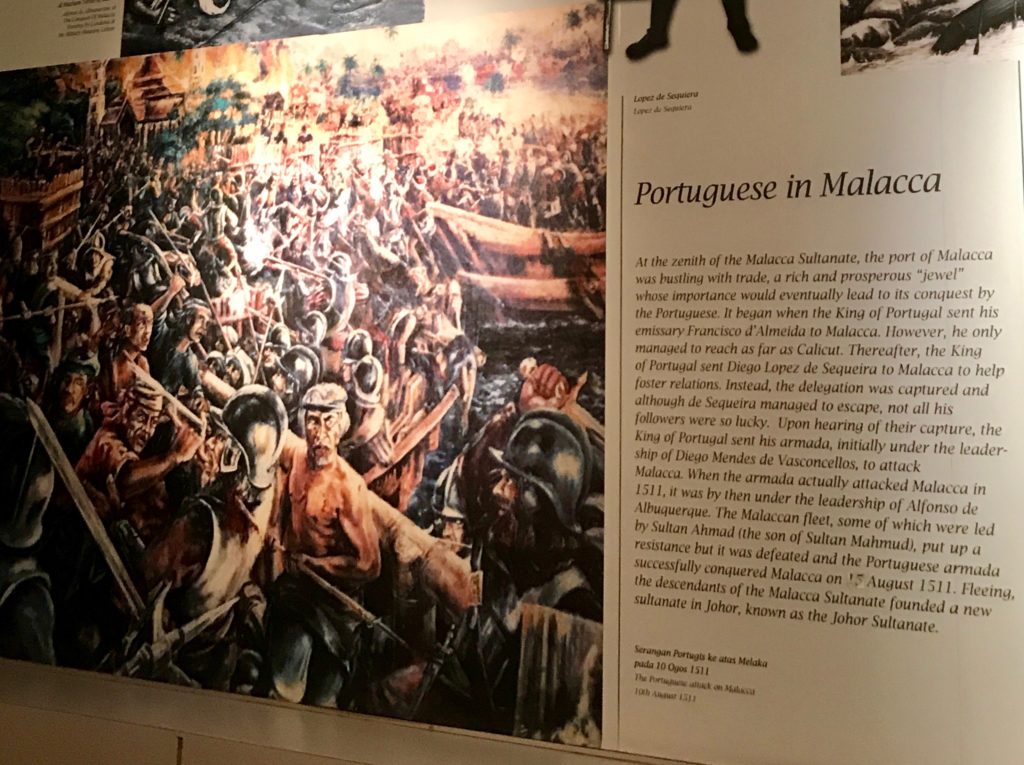

Then came the first wave of foreign intervention with the Portuguese seeking to extend their influence beyond India. In 1511, the Portuguese won a bloody naval battle with the Sultan of Melaka and stayed for 130 years.

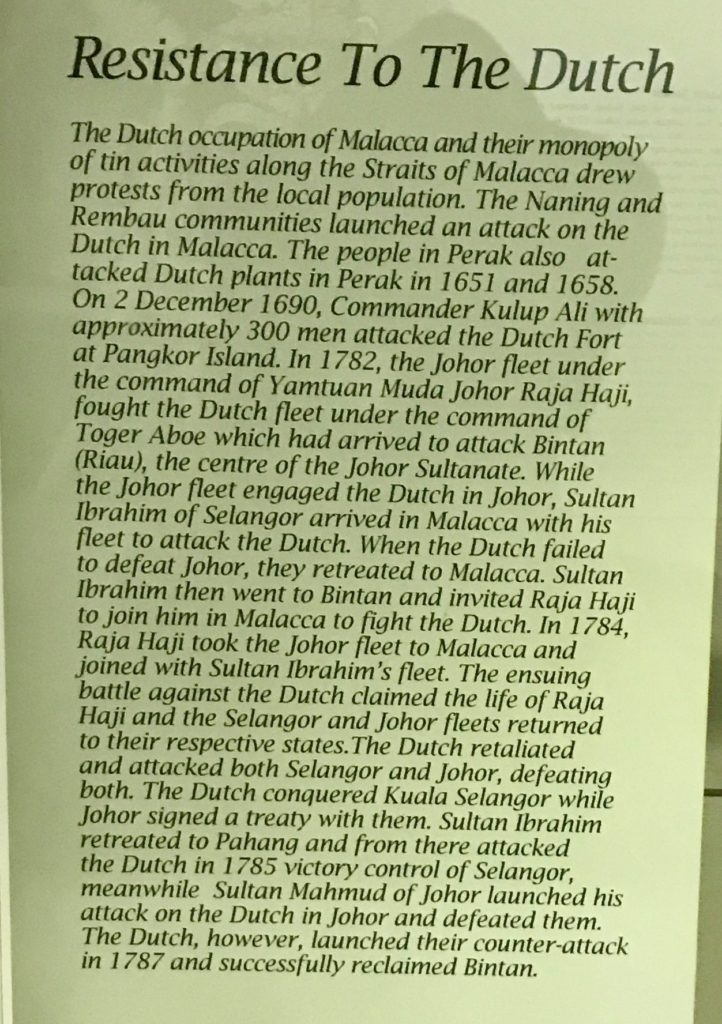

Then came the Dutch. They ended Portuguese control of the Straits of Melaka in 1641, after more battles and loss of life.

Then came the British. They first occupied Penang in 1791 and established a presence in Malacca in 1795. The Pangkor Treaty of 1874 cemented their control of the states, but not after more political squabbling, battles and loss of life.

Then came the Japanese in 1941. That was the shortest period of foreign occupation, ending in 1945 after the Japanese surrender in World War II.

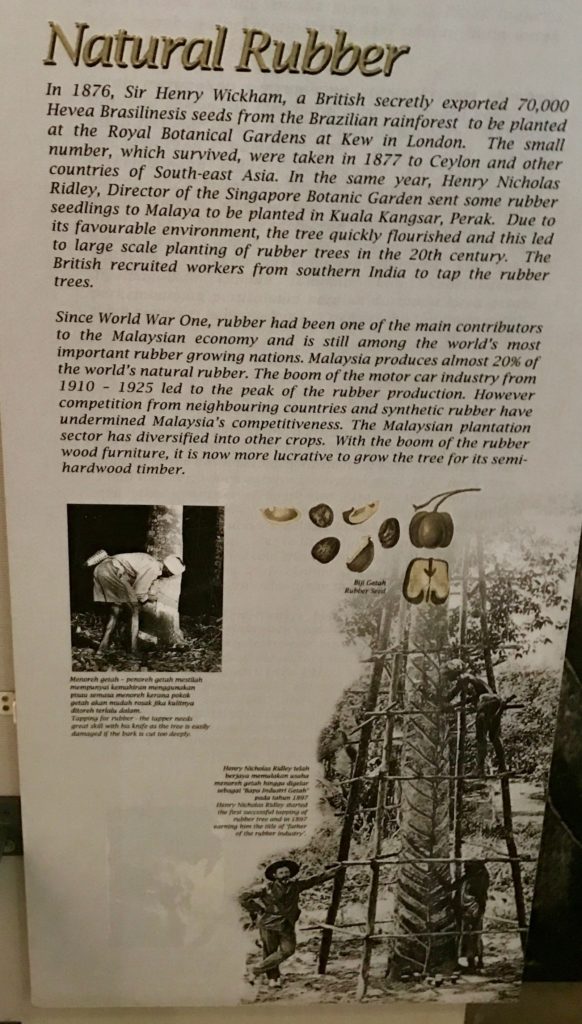

Between these waves, the Chinese came seeking work in the tin mines. The Indians were brought in by the British. Both were required to exploit the commercial opportunities presented by the thriving trade in tin, rubber, coffee, spices and more.

After WWII, a process of coming-together amongst the indigenous Malays began, plus the migrants. The Malaysian Indian Congress was set up in 1946 and Malaysian Chinese Association in 1949.

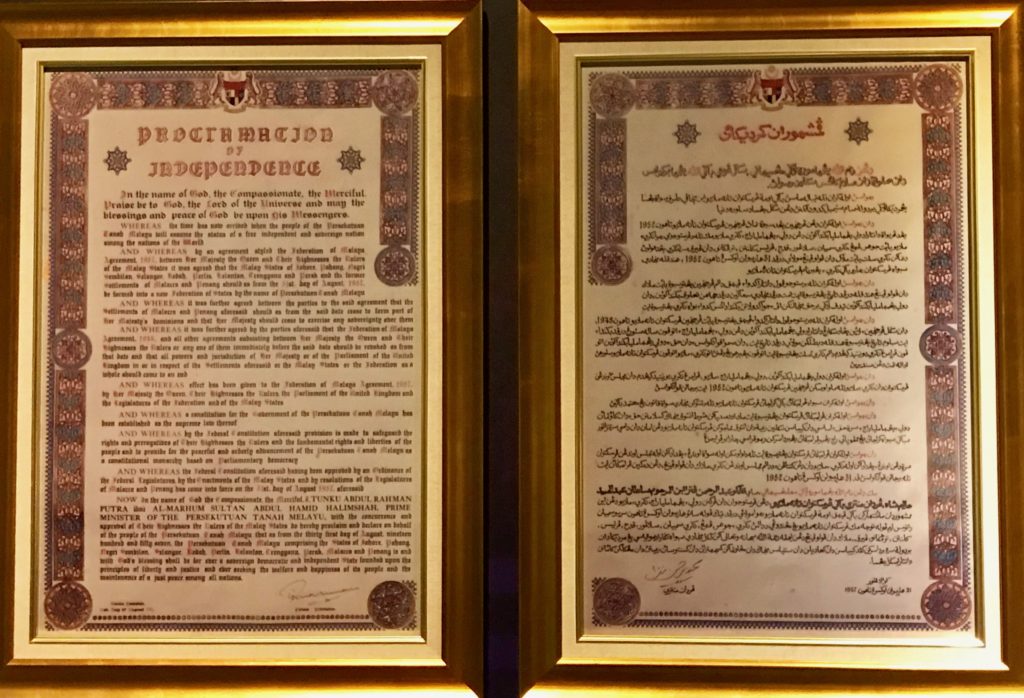

A federation of Malaysian states was set up in 1948 comprising of the 11 states of peninsula Malaysia. A Declaration of Independence was signed in 1957. In 1963, Malaysia was formed including Sabah, Sarawak and Singapore. After only two years, Singapore exited in 1965.

This is Malaysia today, a multi-cultural mosaic of social, cultural, anthropological, religious, ethnic history and heritage. Combined, it is a tourism asset and a major contributor to economic development.

The most important lesson I learnt from the museum visit is that assets can quickly become liabilities for the same internal/external reasons that have remained unchanged over the years – battles for control of territory, power, money, ethnic supremacy, market share, religious, social and cultural differences, political and economic rivalries, interference and invasions by foreign powers.

This is exactly how colonisation by the European powers triggered multiple conflicts over the same periods right across Africa, Latin America and Asia. The circumstances are identical – local enmities and rivalries offer ripe opportunities for foreign exploitation.

The national plan strives to convert Malaysia into a “developed” country by 2020. Economic growth strives to ensure that development is fair and evenly distributed. But beneath the surface, rivalries are rife among the races, religions and states. Foreign interloping is alive and well, today designed primarily to undermine the Islamic world.

The autocratic sultanates of yore have become autonomous states, provinces and districts. Political and economic rivalries are exacerbated by commercial rivalries amongst local conglomerates and foreign multinationals.

One set of conflicts just gets replaced by another. Only the actors change. No matter how much technological, scientific, financial progress is made, how many big buildings come up, or how bountiful the natural resources, the cycle keeps turning.

The Portuguese, Dutch and British colonialists were masters at playing off one Sultan against another. The Sultans, too, never learnt from their mistakes.

The spiral continues. The peace-unity-prosperity ideals of nation building fall by the wayside as history repeats itself. All the slogans, treaties and systems of governance and representation fail.

Today, destroying countries no longer requires naval battles. Simply attacking a currency is enough, as Malaysia and many Asian “tigers” discovered in 1997. Whatever the tools used, the end result is the same – one group seeking to assert its power and authority over another. Those who suffer most are at the bottom of the ladder.

Today’s world order is only a perpetuation of the previous world orders, all of which have led to cycles of violence for largely the same reasons – money, power, land, natural resources, identity, religion, influence, security, ego.

So, what next? How can this cycle be broken?

In hindsight, were any of those battles worth the loss of life and suffering? What long-term good did they do?

In a borderless world, which we are theoretically supposed to be in, free trade, free flows of money and people are supposed to have done away with the military battles for resources. In fact, quite the opposite has happened.

Why is competition necessary at all today?

In pursuit of market share and GDP growth, are countries, religions and companies still part of the problem rather than a part of the solution?

Can one-upmanship be replaced with co-existence based on fundamental human principles based on Mahatma Gandhi’s two famous dictums: “There is enough in the world for everyone’s need, but not for everyone’s greed” and “An eye for an eye will leave the whole world blind”?

Natural disasters, health pandemics and global warming are known as Problems Without Passports. They respect no religions, cultures nor borders, can strike anywhere, anytime, and are phenomenally expensive to fix. Add to that local problems such as corruption, poverty, education and health.

Such common problems prove why inter-faith conflicts are a grotesque waste of time, energy, intellectual resources and, ultimately, money. What difference does it make what one wears, believes in, eats or worships when there are hundreds of more common problems to be addressed?

Another lesson gleaned from the museum is that the world again faces similar circumstances that triggered wars of the past. These wars are started by people who are least personally affected by them. The most suffering is borne by the millions of common people at the grassroots.

A third lesson is that no empire lasts forever.

Today, the United States is clearly on the way out. A new world order is emerging. The much-ballyhooed globalisation has failed to deliver its promised goods. The nirvana era of peace and stability that was supposed to have dawned after the fall of the Berlin Wall and the end of Cold War has also failed to materialise.

ASEAN has a unique opportunity to fill the vacuum and get it right. Other countries in ASEAN have been through the same historical experiences of Malaysia. The French colonialists were active in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia; the Spanish in the Philippines. The Americans are active everywhere.

This year marks the 50th anniversary of the founding of ASEAN. The integration process, built on the foundations of the three economic, socio-cultural and political-security blueprints, is designed to best harness the unique natural, cultural, social, ethnic strengths of the region for the common good.

At a broader level, the UN Sustainable Development Goals strive to set numerical targets to achieve a better quality of life in many different areas.

The region’s indigenous social-cultural-ethnic wisdoms, including the Sufficiency Economy philosophy of the late Thai King Bhumibhol Adulyadej, the three ASEAN blueprints and UN SDGs provide all the background knowledge base necessary to build a new regional order.

ASEAN’s fundamental strengths and assets remain unchanged and unmatched – its geographical advantage, its demographics, intellectual and natural resources. These only become liabilities when manipulated for the same repetitive reasons, and when generation after generation of leaders fail to heed the lessons of history.

The entire principles of development based on “competitiveness” need to be questioned. Whatever short-term problems were solved, they only fanned the flames of discord and disunity and, over the long-term, resurfaced with a vengeance.

The opportunity to break that cycle is again upon us in the second half of the ASEAN Century. If the lessons of history can be learnt, it will be possible to do so perhaps more sustainably and permanently in pursuit of One Vision One Identity One Community.

Liked this article? Share it!