19 Dec, 2018

First Buddhist University conf on SDGs mulls challenge of averting Global Warming AND Global Meltdown

Bangkok – When the Rector of the World Buddhist University (WBU), the Venerable Phra Anil Sakya was invited to speak recently at a conference of bankers and economists on alleviating poverty and implementing the UN Sustainable Development Goals, he asked if they had made a mistake inviting him in the first place. After listening to two hours of talk, “I told them that I should not have been invited here. It was all beyond my understanding. It didn’t make any sense.” Why? Because Buddhist monks take vows of poverty and live below what the UN describes as the poverty line of US$3 a day. So, he asked the bankers, “What do you mean by eradicating poverty? I want to live as a poor person. I don’t have any income. I go out every morning with my alms bowl. Does that make me an obstacle to achieving the SDGs?”

The moral of the story: Bankers seeking solutions to global poverty and ways to implement the SDGs may want to first look inwards before pursuing external solutions. Indirectly, Ven. Phra Anil was challenging them: Who is really living an unsustainable life? Who is really living in poverty? Is poverty defined only in financial terms? Are the SDGs just about economics? He told the bankers their main concern is always the economy. “But if I change to my own language, you will see that hunger, health and conflict are universal human problems, not just the problems of 21st century.”

Ven. Phra Anil narrated this story in his opening address to the first international conference on “The Buddhist Path to Sustainable Development Goals,” the first such event organised by the WBU in cooperation with several partner groupings between 4-5 December 2018. It brought together about 100 leading academics, private and public sector executives and Buddhist leaders for an open dialogue on ways “to ensure the sustainability of the planet, provide social and economic justice and advance the cause of ethical decision-making.” It was also designed to get Buddhist institutions, organizations and networks to highlight the centrality of the cause-and-effect factor and brainstorm ways to become a part of the solution. In the afternoon of the second day, an open discussion was held with the general public.

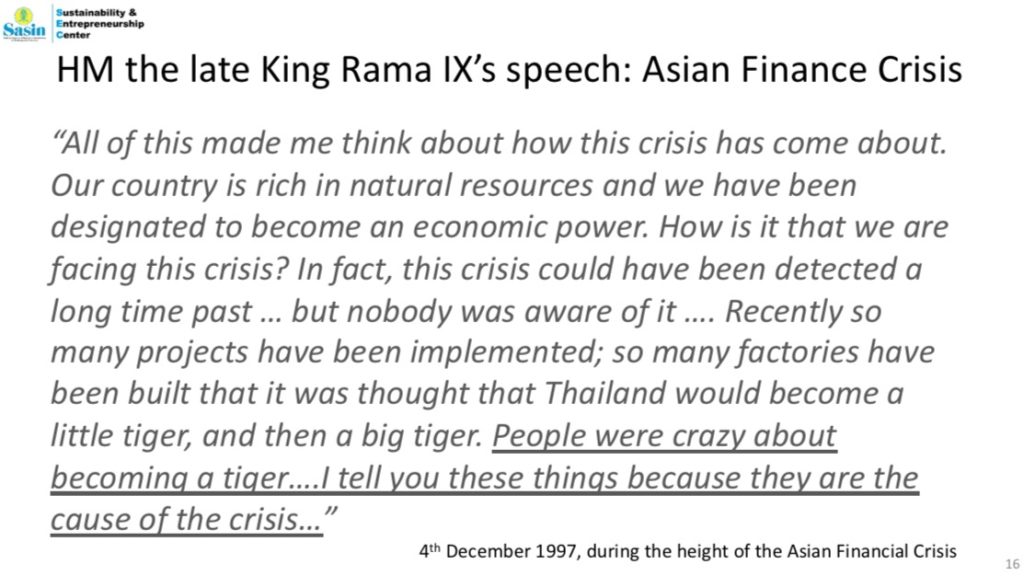

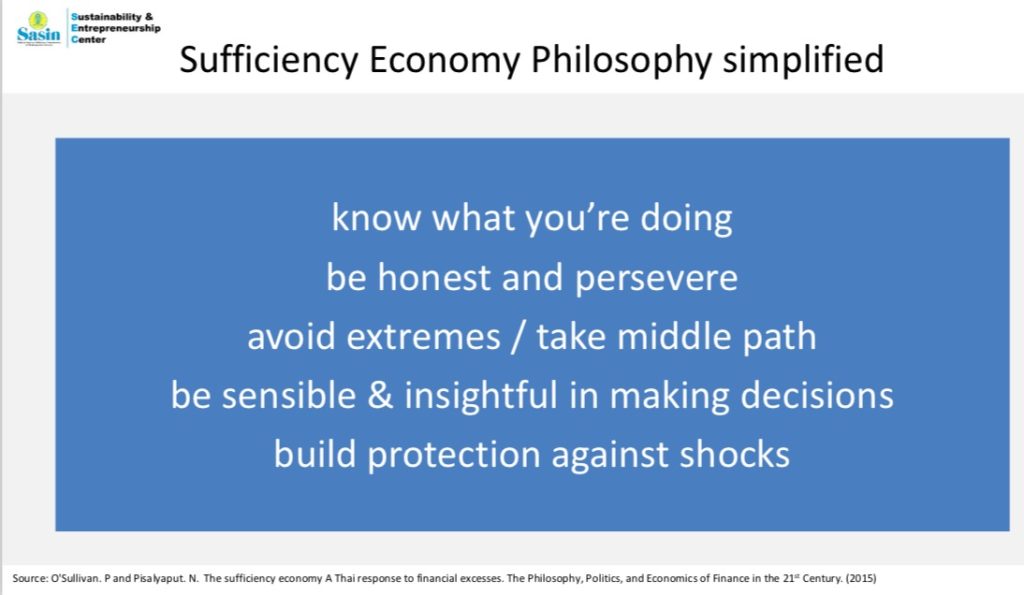

A number of academic dissertations highlighted the moral, philosophical, financial, social and economic linkages between the UNSDGs, Buddhist teachings and the Sufficiency Economy Philosophy (SEP) of Thailand’s late monarch Bhumibhol Adulyadej, the “Development King”. Fulfilling his duty as “King of All the Thai people”, regardless of caste, creed or religion, the late King, free of any pressure to pursue profits or votes, conceptualised the SEP as a secular and sustainable form of human progress, well before the United Nations woke up to it.

Indeed, the conference dates honoured two important Thai occasions: King Bhumibhol’s birthday, 5 December 1927 which is also Father’s Day in Thailand and the late 19th Supreme Patriarch, Somdet Phra Nyansamvara who was born on 3rd October 1913, the founding date of the WBU.

Every speaker stressed how the “development” model adopted over centuries was a total deviation from the Buddhist Middle Path, and never really holistically sustainable. If many of the inventions of humankind were designed to improve the “quality of life”, why is there so much continued conflict, disease, hunger and poverty?

Said Ven. Phra Anil, “There is growing recognition that current economic development policies are neither sustainable, nor do they contribute to happiness. The world is searching for a perfect development model which keeps a holistic vision of human development, a balance between material and mental development, which guarantees GDP as well as Gross National Happiness (GNH).”

Ven. Phra Anil began by pointing out that the Buddha’s first sermon itself was all about sustainability. He said, “Fundamentally, sustainable development is any development which has a balance as its foundation and has no negative by-product on society, economy and environments.’ That is the same root and same meaning as the Sanskrit root of ‘Dhamma.’ In other words, Buddhism is all about guidance on sustainable development. Accordingly, the Buddha’s first sermon, Dhamma-cakka-pavattana literally can be translated as ‘the application of sustainable development in action’.”

He proved this by showing 17 slides, each of which correlated the 17 SDGs to 17 teachings of the Buddha. For example:

Dr. Patrick Mendis, of the Fairbank Center for Chinese Studies, Harvard University, noted that Buddhist teachings applied in equal measure to individuals, communities, societies and countries. He said Buddhists are guided to observe five precepts in fulfilling the primary conditions of Right Livelihood: abstain from killing, stealing, improper sexual relationships, lying, and the use of intoxicants. “Every Buddhist is expected to live a life according to this code of conduct. In practice, however, many Buddhists violate the Buddhist way of life. Many Buddhists in Sri Lanka, Myanmar, Thailand, Cambodia, Korea, Japan, China, Tibet, and elsewhere live life contrary to their own religious and philosophical convictions.”

He flagged how conventional economics espoused by bankers and economists were often in complete contradiction to Buddhist teachings. “Buddhist teachings emphasise that a person who is free from debt and saves wealth for the family and children attains true happiness. They flag the danger of being a slave to accumulating excessive wealth and emotional suffering of harmful possessions — such as the production and trade of lethal weapons, poisons, and alcoholic drinks.”

He added, “The Vyagghapajja Sutta also refers to savings as one of the most important requirements for economic prosperity. These suttas attest that the Buddhist economic philosophy itself is based on frugality, resourcefulness, control over excessive craving and moderate patterns of consumption in the search of balanced material and spiritual life.”

The same guidance applies to ecological and environmental issues. Said Prof Mendis, “When human greed and acquisition of wealth becomes a way of life, it creates an imbalance in human life and in the natural ecosystem. Buddhist teachings advocate a gentle attitude towards the environment and stress the importance of a peaceful, violence-free society. Buddha was born under a tree, attained Enlightenment under a tree, and passed away under a tree, symbolising the close relationship between People and Nature.”

Dr. Emma Tomalin, Professor of Religion and Public Life, University of Leeds, UK, focussed on Gender Equality and Empowerment of Women. She cited a Mahidol university survey showing Thailand’s economic boom in the 1980s and 1990s generated mixed results, especially for rural women who were marginalised as they were squeezed out of their traditional role in agriculture. The same research shows that one in three households in Thailand report domestic abuse; only 4.8% of parliamentary seats are held by women; and Thailand has a large and exploitative sex industry.

In fact, she said, “economic development has increased the size of the sex trade and has created more disparity between the poor and wealthy classes. Men have more disposable income to buy sex and more rural women were forced into the sex industry. This also coincided with the emergence of HIV and AIDS, which not only affected the sex workers but also the wives of the Thai men visiting prostitutes.” Thus, Prof Tomalin said, “it affects all women, where rural women are more likely to become sex workers, but middle-class women also suffer due to the actions of their husbands.”

Dr. Joel Magnuson, an economist based in Portland, Oregon, spoke on the topic of “Changing Our Approach to Economic Change: A Buddhist-Institutional Framework for Sustainable Development.” He noted that there is a growing consensus that the world is entering a tenuous period as economic bubbles have been created via debt. This “artificial wealth” makes people feel wealthy, creates jobs and drive economies. On the flip side, it worsens the rich-poor income gap as fewer individuals control most of the word’s wealth.

Along with an increasingly perilous ecological situation, Dr Magnuson noted, conditions are becoming more dire in all three dimensions: Ecology, Economy and Equity. “The pathological system and conditions originate in economic activity that is habitualised and institutionalised,” he said.

He noted that the Trump era is worsening the challenges of climate change, resource depletion, financial system instability, extreme income and wealth polarisation, and mounting debt. “The crises we face are more extreme and more intractable then they were three decades earlier. Thirty years ago, humans were discharging about 20 billion metric tons of carbon dioxide into the air each year, and by 2017 that figure has risen to 32.5 billion — a new record,” he said.

While there was no disagreement amongst the speakers about the scale of the global problems, the solutions appear distant and tortuous.

The enormous complexity of attaining the SDGs was explored by Prof Dr. Patrick O’Sullivan, Grenoble Ecole de Management, Grenoble, France, in a paper provocatively titled “SDGs: Utopia, Propaganda or Pragmatic Reality?” He said it was all very well to talk of alleviating poverty, but if the goal was to make all the “poor people” attain the standard of living of the average European, it would take 2.7 planets worth of resources to do so. On the other hand, making the population live frugally through “voluntary simplicity” would drive down economies. He noted the emerging perfect storm of problems such as overpopulation, pressure on natural resources, technological complexities and wars, to name just a few.

Prof O’Sullivan noted the challenges of coming up with independent measurement indicators to monitor progress in areas such as peace and society, and at the same time to mitigate the influence of various actors such as political leaders and/or business/NGO leaders “who will chose the indicators that suit their prejudices/campaigns.” He also cited the broad-context realities of rampant consumerism, greed, corruption, gross inequalities and glorification of violence across multiple media channels.

Against this background, he said, “Buddhist values of the middle way, peaceful coexistence with all living beings, and of sufficiency economy can play a central role in creating the political and moral environment that is conducive or indeed essential to the practical attainment of the SDGs.”

To understand the full significance of this design, please click on the image to download the conference booklet.

Dr Stephen Young, Executive Director, Caux Roundtable for Moral Capitalism, focussed on the key linkage between the SGSs and “moral governance.” He wrote in his paper: “The SDGs are our priorities for action. They are … justified by the deepest morality, one which resonates in all cultures and faiths – that human life is a good to be valued and enhanced. The more we implement them, the more we will be successful in improving the life, liberty, and happiness of humanity.”

Elaborating, he said, “moral governance focuses our use of power and willfulness on the good. It implies that governance is stewardship and not exploitation. It demands that power be measured not by its strength but by the ends to which it applies its strength. This is true for individuals as well as for collectives — families, villages, corporations, nonprofits, churches, sovereign authorities. Governance is the exercise of that capacity for self control which makes human happiness possible. No one out of control can be happy.

“Lack of moral governance is self-destruction. In particular SDG 16 aims to ‘promote peaceful and inclusive societies for sustainable development, provide access to justice for all, and build effective, accountable and inclusive institutions at all levels.’ SDG 16 thus places attention on the trust responsibility of public government to nourish and protect social and human capital for our use. By reminding us of the necessity of having moral governments in our institutions of public power, SDG 16 puts us on notice that moral governance is a fundamental human good.”

Mr. Poomjai Nacaskul, Senior Vice President, Siam Commercial Bank, examined the notion of risk, particularly as enshrined in mainstream financial risk management methodologies. He noted that dating back to the days of Greek mythology, risk was seen as being somewhat heroic, a challenge to be overcome. This led to the antecedent modern-day incantation “no risk, no reward”. “Taking on and getting the best out of risky challenges represented a rite of passage, a coming of age for an individual protagonist with grand destiny.” He noted the different kinds of financial and monetary risks and the various kinds of measures used to manage and – or mitigate those risks.

Mr. Poomjai noted that “the very success of free-market capitalism has led to unprecedented rise in global financial and economic complexities, thereby limiting the “shelf-life” of static assumptions-rich risk management models and methodologies.” He said the SEP flags the need to be vigilant of the operating rationality, to re-examine the implicit model/parametric assumptions, and to prepare for the inherently unforeseeable yet existentially unavoidable.”

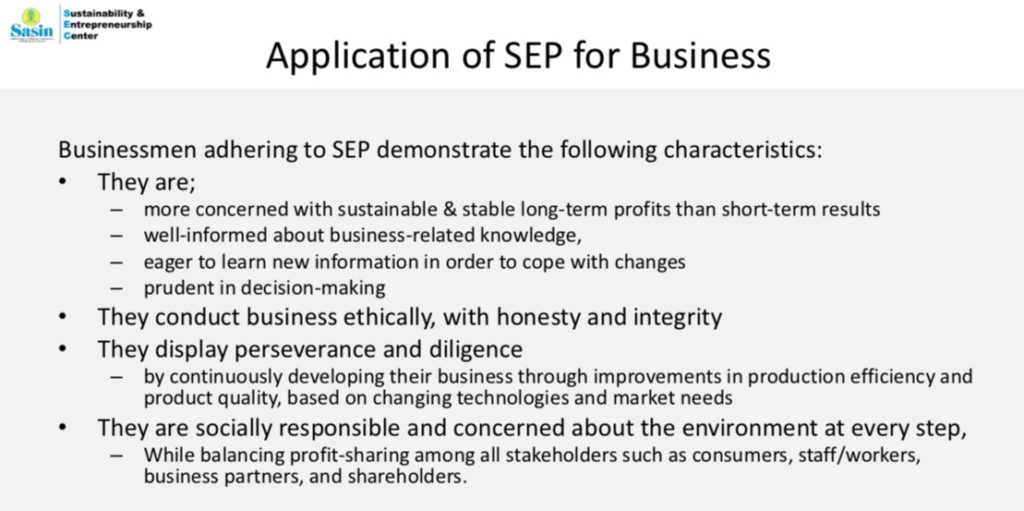

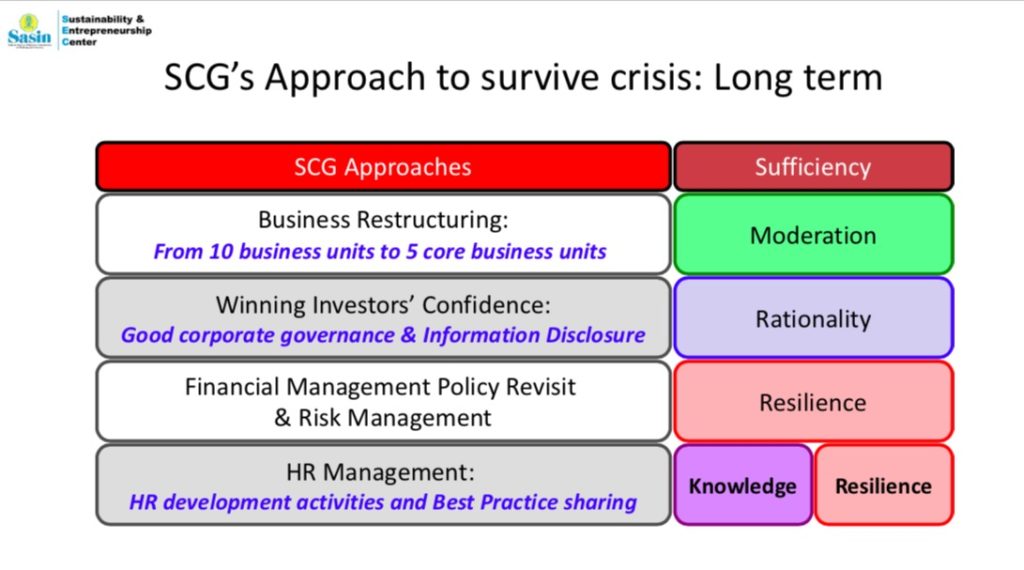

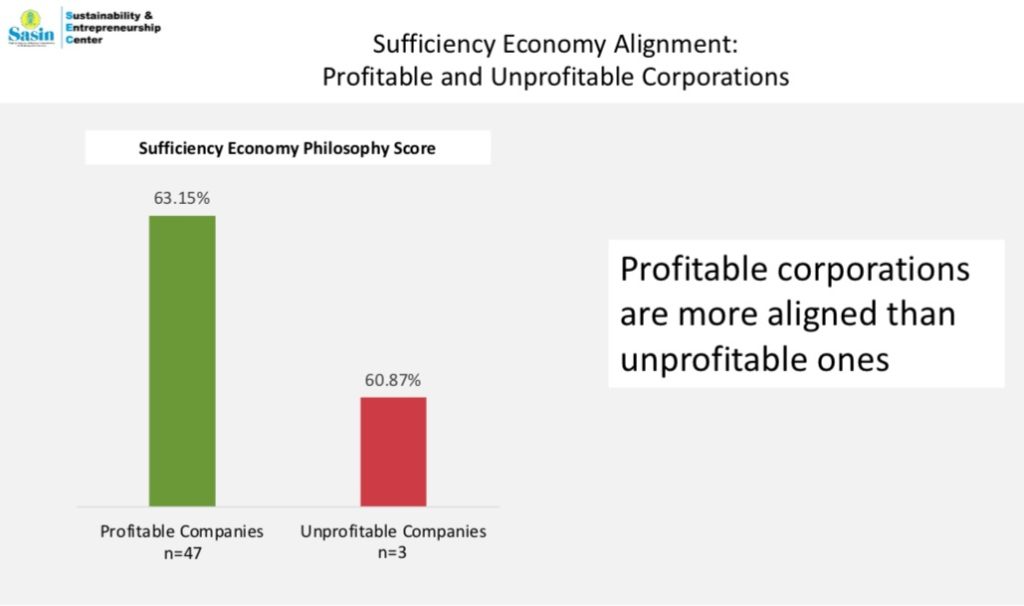

Researchers Nick Pisalyaput and Vasu Srivibha of the Sustainability and Entrepreneurship Center, Sasin School of Management, presented a paper with Case Studies on Dharmic Sustainability at Work in Thai Companies. This was ground-breaking research into Thai companies which have applied the SEP in their corporate strategies, and generated a direct financial result. They presented what they said was the first case study of the Siam Cement Group, one of the largest Thai conglomerates, and how it recovered from the infamous and ruinous 1997 financial crisis by adopting a new business perspective based on the Sufficiency Economy Philosophy.

Vasu Srivibha and Nick Pisalyaput

Before the crisis, the SCG had 10 different business units with an average net profit of 4-5 billion baht. However, the financial crisis led to a ballooning of its corporate debt and billions of baht in corporate losses. In the restructuring that followed, the company focussed on human resource development, relying on good and capable persons with both knowledge and morality. The three core values of Moderation, Reasonableness and Resilience were applied company-wide, from the board of directors all the way down to finance, risk and resource management. Instead of lay-offs, the company adopted stringent cost control, increased work efficacy, leadership development programmes, enhanced recognition of the role of employees in solving company problems, and more.

The researchers have also studied how other Thai publicly-listed companies are growing their adoption of the SEP in their business conduct and operations. They said there is growing evidence that companies which pursued a better balance between profits, sustainability, good governance, risk mitigation and social responsibility had higher levels of profitability than those which didn’t.

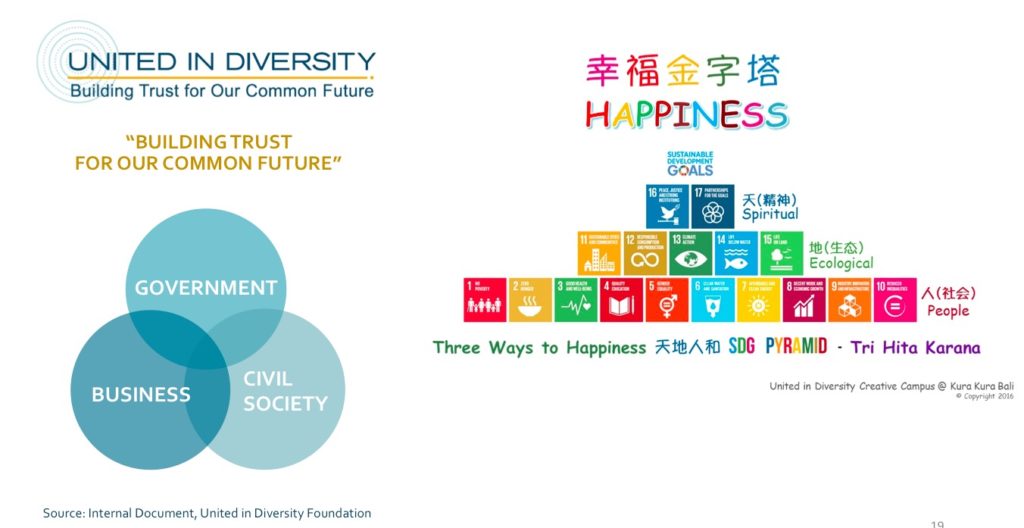

Other countries in ASEAN are also seeking solutions aligned to the SEP and SDGs, albeit under different name-tags. In Indonesia, it is known as Tri Hitana Kirana (Three Ways to Happiness).

Dr Indira P Baheramsyah, CEO, The United in Diversity Foundation, noted that Indonesia was also as seriously impacted as Thailand by the 1997-98 economic crisis. As one of the world’s most populous countries, Muslim-majority Indonesia is facing enormous social, economic and environmental pressures. The current Unity in Diversity agenda is to promote development by building trust and cultivating leadership, she said.

The philosophy of Tri Hitana Kirana involves restructuring the SDGs into a three-level pyramid that divides the 17 goals into spiritual, ecological and people categories. These can then be applied to address the “Three Divides”: Eco-Divide (between Self<>Nature); Social Divide (between Self<>Other) and Spiritual Divide (between Self<>Self). Implementing this will require strong collaboration between government, private sector and civil society, she said. This October, Dr Indira organised a Tri Hitana Karana forum alongside the World Bank/IMF annual general meetings held in Bali to take the case to global bankers.

Basically, the conference ended with most important conclusions: 1) More than 2,500 years ago, a prince-turned-pauper voluntarily opted out of living luxuriously and became a lowly commoner, setting out clear guidelines for humanity to live peaceful, happy, sustainable lives; 2) his guidance has largely been ignored over the centuries; 3) many countries and societies are suffering from the cause-and-effect consequences of ignoring that selfless advice; and 4) the rot that has set in is so widespread in depth and breadth that stopping, mitigating and reversing it is going to be a monumental task.

Similar to the move towards alternative energies to alleviate global warming, a shift to alternative development pathways is now seen as being imperative to avert a potentially far wider and disastrous global meltdown. That shift is now under way, and will decide the future of humanity over the rest of this century.

Travel Impact Newswire Executive Editor Imtiaz Muqbil was the only travel industry journalist invited by Ven Phra Anil to cover this historic conference.

Read also:

Liked this article? Share it!