9 May 2019

More preaching to the converted at the PATA Annual Summit 2019

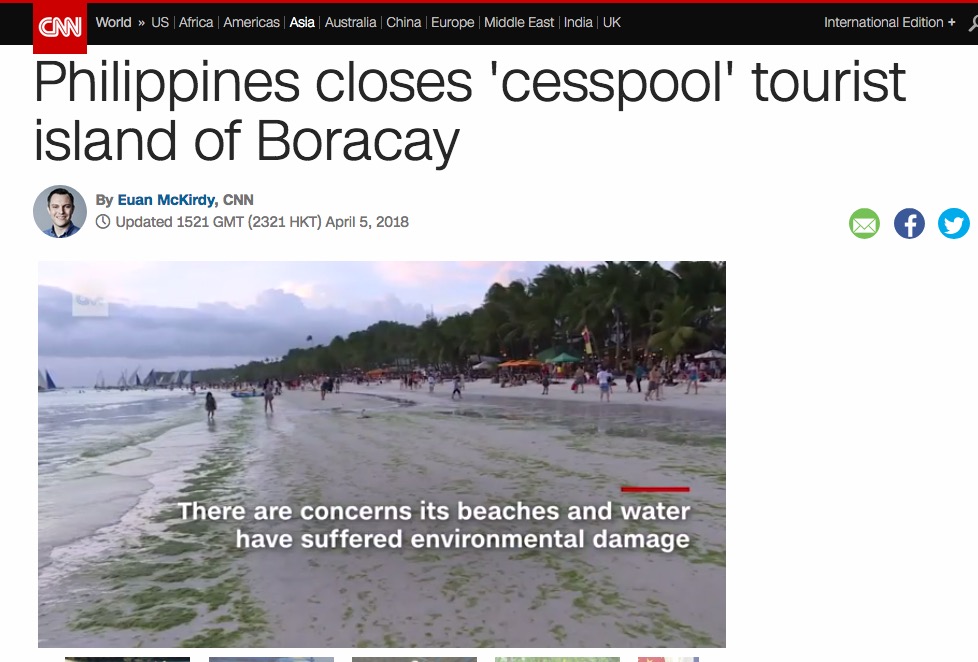

In April 2018, the Philippines announced a six-month closure of Boracay, a draconian order unprecedented in the history of Asia-Pacific tourism. Referring to it as a “cesspool”, President Duterte ordered the shutdown to facilitate the cleanup of an island once grandiosely cited in the tourist brochures as being “pristine” and “unspoiled”. The move triggered a massive controversy in the Philippines. Although the local economy suffered the serious short-term pain of job losses and dislocation, it is widely recognised today to have generated a fair degree of long-term ecological gain. Scared of being next on the Presidential hit-list, other Philippines beach destinations hastily undertook voluntary clean-ups.

As the closure order marks its first anniversary, this month’s convening of the annual summit of an organisation that claims to be the “Voice” of Asia-Pacific tourism would have been a perfect platform for a heavyweight debate and discussion of its pros and cons, and a valuable learning experience for other destinations grappling with similar challenges. And yet, the programme of the PATA summit in Cebu this week downplays what was one of the biggest travel stories of 2018. The closest Boracay may come to being featured is a talk on “Destination Management in Times of Uncertainty” by Arturo P. Boncato, Jr., Undersecretary, Tourism Regulation Coordination & Resource Generation, Department of Tourism. This, in an event advertised as being a gathering of “thought leaders, industry shapers, and senior decision-makers who are professionally engaged with the Asia Pacific region”.

PATA CEO Dr Mario Hardy wants to position PATA as an “exponential thought leader, a trusted partner and an effective advocate for the travel and tourism industry to, from and within the Asia Pacific region.” He says “PATA needs to be at the centre of all discussions relating to the uncertain world our sector is facing – and its future. Every PATA employee, advisor, executive board member needs to become an ambassador of exponential leadership.” He says one of PATA’s core principles should be to “remain sharply focused upon making the Association relevant and impactful.”

That is never going to happen if PATA cannot realistically prioritise the region’s challenges. Last year, for example, PATA was making a big deal of the European GDPR. This year, nobody can even remember it existed. Indeed, Boracay is not the only contemporary topic missing on this year’s summit. There are at least four others which, if included, would have the elevated the content agendas of travel & tourism industry events to a whole new level:

The impact of natural disasters: The Philippines is one of the world’s worst-hit countries by hurricanes, typhoons, floods, earthquakes and volcanoes. They exact an enormous human and financial cost, and impact on visitor arrivals. How the Philippines deals with these would have been worth a dedicated session in its own right. Mr Arturo may well cover this, too, but he is only one of three panelists in a 40-minute session, which will barely do it justice.

Migrant labour: The Philippines is one of the biggest global exporters of migrant labour. Millions are employed in travel and tourism, especially in the Gulf countries and as well as on cruise ships. Many are now seeking jobs closer to home in the ASEAN region. As travel & tourism is focussing heavily on human resources development, the future of migrant labour is a key issue in an era of changing demographics and expanding robotics.

Alternative Perspectives: The Philippines has some of Asia’s most vibrant civil society activist movements. They produce voluminous amounts of well-researched information on development trends and provide early warnings of what could go wrong. Giving the Asia Pacific travel industry “thought leaders” a chance to hear some vital check and balance perspectives would have gone a long way towards expanding mind-sets and bolstering the summit theme of “Progress with a Purpose”, which is specifically designed to advance “development for the benefit of society and humanity as a whole.”

Safety & Security: In the same forceful way he shut down Boracay, President Duterte has also launched a “war on drugs” that has led to the extrajudicial deaths of thousands of alleged drug dealers and users, according to human rights watchdog groups. The president sees drug dealing and addiction as “major obstacles to the Philippines’ economic and social progress.” This, too, has raised serious moral, ethical and legal questions. Has it made the Philippines any safer as a tourism destination?

None of the above are explicitly included on the Summit programme, but will almost certainly come up in dribs and drabs. On the surface, the Summit flags the usual motherhood-and-apple pie topics that can be found anywhere. The traditional keynote speech on the global economy is being delivered by a representative of The Economist Global Network. An equally good, and probably far more regionally relevant, presentation could have been made by the Manila-based Asian Development Bank. Professor John Koldowski, the Special Advisor to the CEO, will deliver his annual number-crunching report on visitor arrivals and forecasts. His forecasts have never forecast a downturn. The future picture is always rosy even though, as Dr Hardy himself says, “In times of increasing change and complexity, it can be difficult to envision bold new futures with any certainty.”

The closing keynote speech on the ho-hum topic of sustainable destination branding is being given by the head of the Slovenia Tourist Board. What exactly are Asia-Pacific destinations supposed to learn about sustainability from a country that did not even exist until 1991? The star attraction is the Chief Strategy Officer of Airbnb, a brand-name which always attracts a lot of wide-eyed attention. If history is any guide, “presentations” by these brand-name executives are well-sanitised, marketing bombast. In fact, a number of summit speakers have a slot more because of their membership-revenue value to PATA.

The UNWTO/PATA Leaders Debate also leaves much to be desired. Speakers will “debate” which of the 17 UN Sustainable Development Goals “can make the biggest impact.” A “debate” is technically a contest between two opposing points of view. The SDGs do not lend themselves to a “debate”; they are all relevant and important, from different perspectives. Anyone who has closely followed the SDG trail (as I have), especially the back-room politics, would know that the real issue up for debate is the means of achieving the SDGs, not which SDG can “make the biggest impact.” However, putting the SDGs on the PATA summit agenda is in itself a positive step for which I can claim some credit. Last November, I covered the PATA Destination Marketing Forum in the Thai province of Khon Kaen and criticised the zero mention of the UN SDGs. Bingo. The SDGs are suddenly very much on the agenda in Cebu.

On 25 April, PATA announced that the Summit was “sold out”. That was hardly a surprise, given the fact that PATA members could attend free. The total delegate turnout listed is about 300, including 50 host delegates, and about 100 others who sit on the various PATA committees. After totalling up the students, the final turnout will probably not be very different from the 372 delegates who attended last year’s summit in Korea.

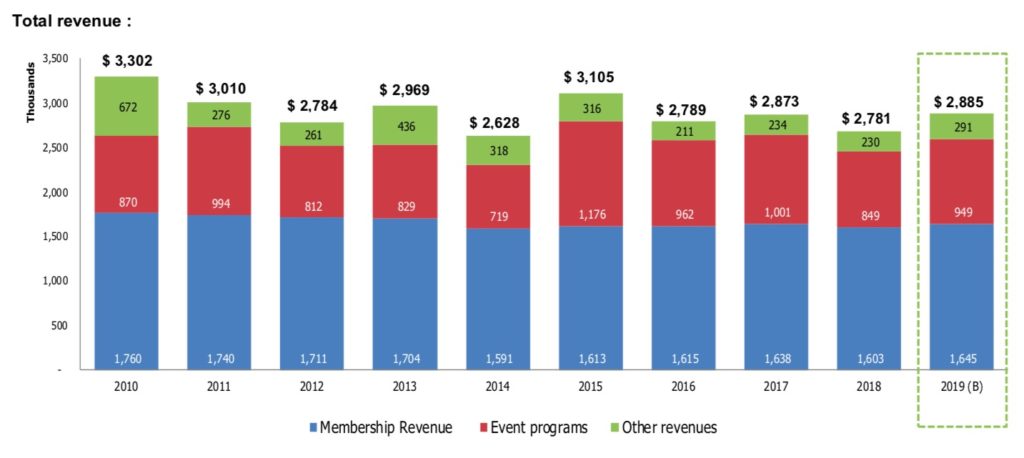

This dichotomy between the “talk” and the “walk” sheds some light on another reality. Behind closed doors, the PATA board members will be told that while Asia-Pacific travel & tourism is growing robustly, PATA’s revenues and membership both dropped again in 2018 — a clear indicator that PATA’s search for a unique selling proposition is faltering. In the last four years, the Association lost two major NTOs and three major airlines. One, the Australian Tourist Commission, was a surprise. In the 1990s and the first decade of this century, senior executives of the ATC were among the most active participants in PATA. NTOs pay a higher category of dues, which is why recruiting new NTO members like Slovenia and Ras Al Khaimah is critical.

To analyse the reasons for its membership stagnation, PATA studied why 527 members worth a total of $712,167 had pulled out in the past 4 years. It was found that 58% (275 members or 70 members per year) had been members for less than 2 years and many were members for just one year. PATA says, “On this historical basis, up to 60% of members recruited this year will terminate next year. To improve the member retention ratio, we need to be focus more upon how to expand the loyalty period of industry members (90% of these terminations were in the Industry category).”

That will require PATA to find a unique selling proposition. In its pre-Internet heydays, PATA had distinct competitive advantages. It’s global membership of 17,000 cutting across all the chapters provided unmatched networking opportunities to build a business. It had two apex events on the Asia-Pacific calendar – the Annual Conference and the PATA Travel Mart. Today, all these advantages have dissipated. Hundreds of travel conferences and trade marts are being held at any given time worldwide. More direct competitive threats are on the way. The Singapore-based ITB Asia, which eclipsed the PATA Travel Mart as the region’s leading trade show 10 years ago, has just announced that it is going to be clustered with a MICE show. That will pull in more numbers, giving both buyers and sellers better value for time and money.

It is a self-perpetuating vicious cycle. More than 80% of the PATA revenues comes from events and membership. Most events are subsidised by host destinations which seek a marketing RoI based on quantifiable numbers. They have little stomach for realistic debate on issues that advance the cause of “Progress with a Purpose”. Devoid of critical thinking and challenges to conventional wisdom, PATA events — and in fact travel industry events worldwide — become exactly what I have long branded them: Clubs of mutual back-thumpers preaching to the converted.

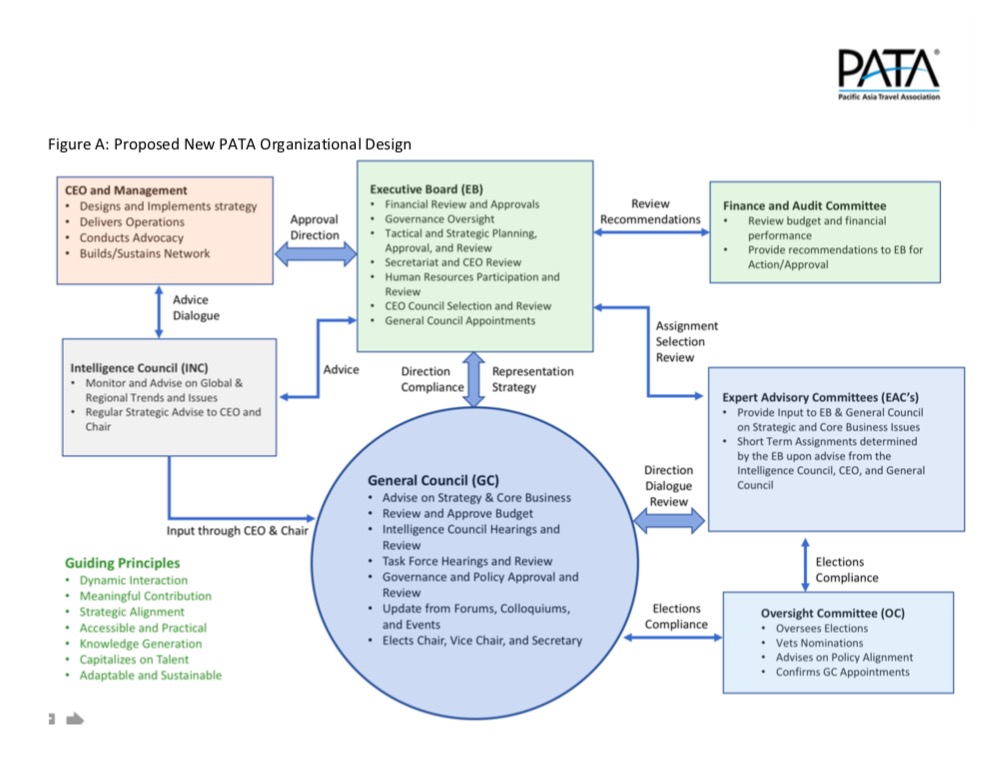

One major change set to be effected is a revamp of the current organisational structure. An extraordinary general meeting has been called to discuss a proposed new organizational model of governance “to further advance the Association in enhancing meaningful and actionable dialogue and collaboration.” To find time for this EGM, another long moribund event was sacrificed, the PATA Chapters Colloquium. According to the working papers, the aim of the proposed PATA governance revisions is to:

(+) Increase engagement of board members, to provide quality input to the Executive Board and management.

(+) Ensure there is strategic alignment between the agendas/deliberations and the organisation’s business plan.

(+) Improve definition of the roles of, and outcomes required from each level of the organisation structure to ensure all are aware of their potential contribution and responsibility.

(+) Eliminate non-productive meetings/committees.

(+) Utilise small action groups to review, in detail, specific terms of reference, and provide quality feedback for action by the Executive Board and management.

This is what the new structure is going to look like:

Whether this convoluted work-flow produces results remains to be seen. Having followed PATA for nearly 40 years, and seen it go through many such organisational overhauls, all backed by the same orgasmic management cliches, I can confidently predict that this new structure will soon become a victim of its own paper-shuffling complexity.

What PATA needs most are people whom it hates the most — critical thinkers who can challenge conventional wisdoms and brutally tell the association where and how it went wrong since moving to Asia exactly 20 years ago. The problem is: Futurists, visionaries and thought-leaders simply can’t stand being told they were wrong, and are continuing to get it wrong.

Which is exactly why the more things change, the more they will remain the same.