16 Jan, 2012

World Economic Forum Lists 50 Biggest Global Risks, Cites “Seeds of Dystopia”

The 7th Global Risks report issued by the World Economic Forum last week could be a watershed in the history of such reports. Alongside a listing of 50 of the most pressing risks facing the world, the report for the first time mentions the word “dystopia”, defined by the Oxford dictionary as “the opposite of Utopia; an imagined place or state in which everything is unpleasant or bad, typically a totalitarian or environmentally degraded one.”

For those in the travel & tourism industry who have never heard of this word, this would be a good time to get used to it. With global stability now the exception, not the norm, trumpeting industry “resilience” may not serve the purpose for much longer.

If the first decade of the 21st century was rife with crises and instability, the second is likely to be even worse.

If the first decade of the 21st century was rife with crises and instability, the second is likely to be even worse.

Download the full report and watch the videos here.

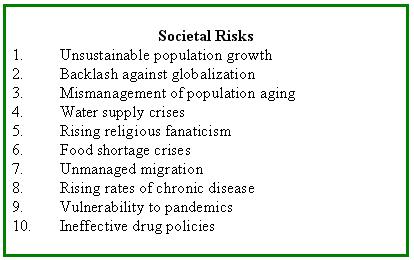

The report devotes one case study to examining what it refers to as the “Seeds of Dystopia.” The introduction says, “The word “dystopia” describes what happens when attempts to build a better world unintentionally go wrong. This case considers how current fiscal and demographic trends could reverse the gains brought by globalization and prompt the emergence of a new class of critical fragile states – formerly wealthy countries that descend into lawlessness and unrest as they become unable to meet their social and fiscal obligations.

“Such states could be developed economies where citizens lament the loss of social entitlements, emerging economies that fail to provide opportunities for their young population or to redress rising inequalities, or least-developed economies where wealth and social gains are declining. This case shows that a society that continues to sow the seeds of dystopia – by failing to manage ageing populations, youth unemployment, rising inequalities and fiscal imbalances – can expect greater social unrest and instability in the years to come.”

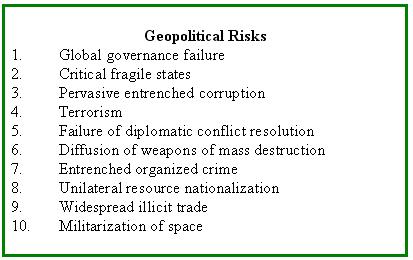

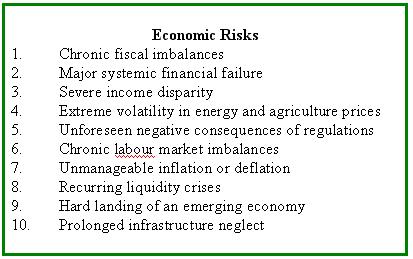

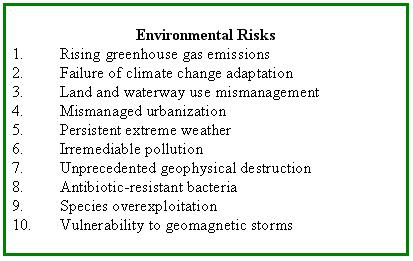

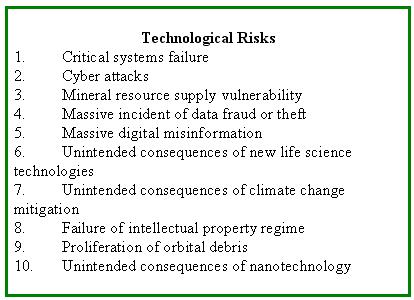

Intended to set the stage for the annual World Economic Forum in Davos between 25-29 Jan, the Global Risks 2012 report is based on a survey of 469 experts from industry, government, academia and civil society. The top 10 risks are classified in economic, environmental, geopolitical, societal and technological categories. The “Seeds of Dystopia” is the first of what the report calls “three distinct constellations of risks that present a very serious threat to our future prosperity and security.” The other two focus on 1) global safeguards (“the capacity to manage the systems that underpin our prosperity and safety”, and 2) Connectivity, especially its “dark side”, the vulnerability of daily life to cyber threats and digital disruptions and the impacts of crime, terrorism and war in the virtual world. All the 50 risks are interconnected in 449 different ways.

In his introduction, Klaus Schwab, the WEF Founder and Executive Chairman, says, “Across every sector of society, decision-makers are struggling with the complexity and velocity of change in an increasingly interdependent world. The context for decision-making has evolved, and in many cases has been altered in revolutionary ways. In the decade ahead, our lives will be more intensely shaped by transformative forces, including economic, environmental, geopolitical, societal and technological seismic shifts. The signals are already apparent with the rebalancing of the global economy, the presence of over seven billion people and the societal and environmental challenges linked to both. The resulting complexity threatens to overwhelm countries, companies, cultures and communities.”

An entire chapter is devoted in the report to the Fukushima nuclear disaster in March 2011 as an example of the catastrophic crisis facing the world and the “unforeseen consequences (which can) ripple through complex global systems”. A natural calamity struck a nuclear power plant, a collision between an “act of God” and a form of energy that was being touted as a future replacement for fossil fuels. Suddenly, everything changed. In addition to the billions of dollars worth of damage and the crisis-response gridlock in the Japanese government, nuclear power was no longer a flavour-of-the-month panacea.

Even after dividing the list of 50 global risks into various boxes, charts and grids, the report offers no solutions; they are to be the subject of future discussions. According to Lee Howell, Managing Director, Risk Response Network, “An important aim of Global Risks 2012 is to help decision-makers evaluate complex risk events and to respond proactively in times of crisis.” Board members, risk executives and policy-makers at the highest level are to meet at Forum events throughout 2012 to discuss “resilient global risk management”. They will also discuss the risks in their regional, country or industry contexts by launching task forces and initiatives designed specifically for their mitigation.

Mr. Schwab notes that “We need to explore and develop new conceptual models which address global challenges” especially as “none of the global risks highlighted respect national boundaries.” He says the report “aims to improve public and private sector efforts to map, monitor, manage and mitigate global risks. It is also a “call to action” for the international community to improve current efforts at coordination and collaboration.”

Diagnosis done, Now for the Treatment

The search for solutions, however, will be long and hard for four reasons – all of which, like the risks themselves, are interconnected. Having allowed the “sickness” to reach this stage, the “treatment” is likely to be even more complex and drawn-out.

Reason One: The first of the 10 geopolitical risks refers to the issue of global governance failure. That could be safely assumed to mean international institutions such as the United Nations, International Monetary Fund, the World Bank, the World Trade Organisation, etc. These organisations are facing calls for serious reform, especially from the developing countries. These reforms are being resisted by the developed countries which do not want to let go of their power or interests. The frustration this breeds is in itself a risk. If small people are rising up in the streets against dictators in individual countries, small countries are also protesting against what they believe to be top-down high-handedness by the industrialised countries and the institutions of global governance that they dominate. Hence, the failure of global governance.

Reason Two: The report refers to “unintended consequences”. This is a questionable comment. While the consequences may have been unintended, they were neither unpredicted nor unknown. There was no shortage of warnings about the negative outcomes of existing policies. The policy– and decision-makers at the WEF chose to ignore groups such as the NGOs, trade unions, environmentalists and even top social scientists and economists. The reference to “unintended consequences” seems to be a clear effort to duck responsibility for the failure of those policies. The WEF message is that the intention was good but if the results did not quite match the intentions, that cannot be helped.

Reason Three: The report is devoid of any references to the consequences of militarism and war. This is an incredible omission, especially given the fact that military conflicts are the result of geopolitical controversies and long-standing injustices that diplomacy has failed to resolve. As global military expenditure is estimated at US$1.6 trillion a year, it is amazing that the massive ripple effects caused by continued conflict does not even rate a mention as a risk. Instead the report classifies proliferation of weapons of mass destruction as a risk, which in a way appear to justify the military adventures claimed to be necessary to control their spread.

Reason Four: Finally, there is no appetite for self-blame. Many of the leaders who attend the World Economic Forum are the same bankers, corporate CEOs, bureaucrats and politicians whose cronyism, corruption and nepotism is responsible for the collapse of Merrill Lynch, Goldman Sachs, Bear Stearns, and other such giant companies which were once considered leaders in their respective fields and “too big too fail”. How can those who could not ensure the survival of their own companies, and messed up the finances of their own countries, be entrusted to create “new conceptual models” and a just, equitable and well-balanced world order? Indeed it would be fair to ask why the regular WEF participants failed to see these problems emerging well before they reached the stage of being at the doorstep of dystopia.

The participants in the World Economic Forum in Davos have yet to recognise that they are the 1% that the remaining 99% are protesting against in the form of the Arab spring and the “Occupy movement.” The 50 global risks listed in the WEF’s 7th Report proves why they are the target of the protest. It is in effect a tacit self-indictment and admission of failure. More problems are looming as those who created this risky global scenario seek to protect their personal interests and positions and duck accountability for the failures of the past.

Liked this article? Share it!